Music and Texts of GARY BACHLUND

Vocal Music | Piano | Organ | Chamber Music | Orchestral | Articles and Commentary | Poems and Stories | Miscellany | FAQs

Concerto in D flat for Piano and Orchestra - (2017)

in memory of Leonard Stein

In the 1974, I was asked by Leonard Stein to perform for the Schoenberg Centennial at the Monday Evening Concerts of the Los Angeles Art Museum. In addition to the early published songs with opus numbers included in that concert, he also put on the program the then-unpublished songs, Gruß in die Ferne, Ein Schifflied (Drüben geht die Sonnen scheiden), and Die Beiden. Also included were the Streichtrio and Fantasie für Violine und Klavier. It is a coincidence that my first composition teacher, Dorrance Stalvey, was both on the faculty of Immaculate Heart College, and also was director of the Monday Evening Concert series at the art museum.

Leonard Stein

Leonard Stein is best known as Schoenberg's editor for Style and Idea, as well as for his work editing Structural Functions of Harmony. In his preface he says of Schoenberg, "It may be true, as some critics claim, that Schoenberg is essentially a preserver of traditional values rather than the revolutionary he is popularly supposed to be. Unlike most preservers of the past, however, who only seek, by historical or stylistic references, to codify theory within a closed system, his concepts, though rooted in tradition, are vital to our time because they derive from the resources of an ever-enquiring and constantly growing musical intellect."

Leonard Stein, in "Preface to the Revised Edition," of "Structural Functions of Harmony," Arnold Schoenberg, Norton, 1969. But alongside the notion of slipping away from "codified" rules, I have pleasant thoughts of rehearsing with Leonard at his home on Carman Crest Drive, after which he would open a bottle of Piesporter Goldtröpfchen, examine many original manuscripts of Schoenberg, and talk of music and music and music, much to my delight. [ 1 ]

For his long association with Schoenberg, he was curator of the Schoenberg archive when at UCLA, headed the Schoenberg Institute when created at the University of Southern California, and then passed all on to the Arnold Schönberg Center which was created in Austria, with a website from which one may examine some of the early scores to which I was introduced decades ago.

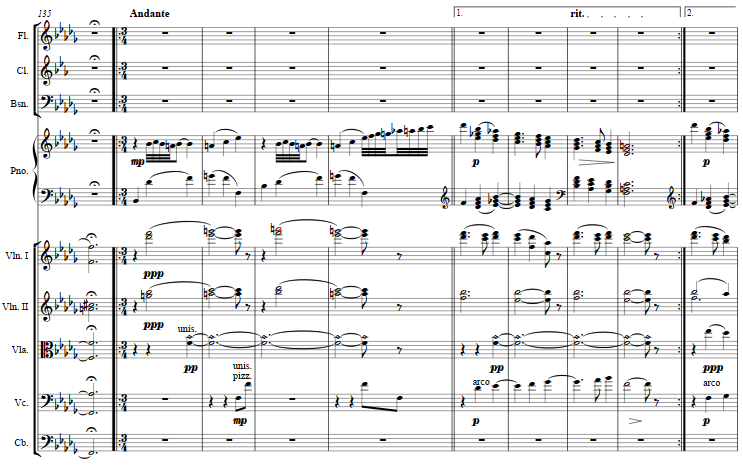

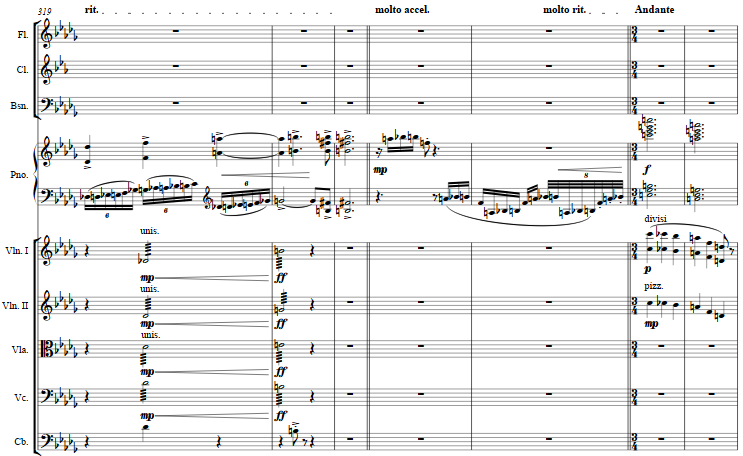

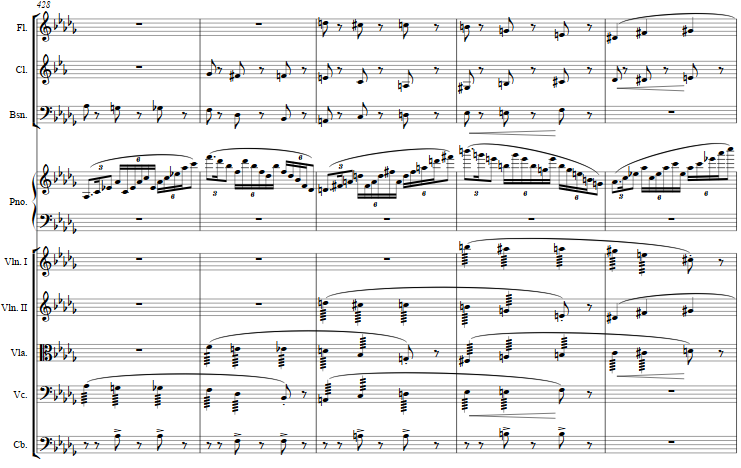

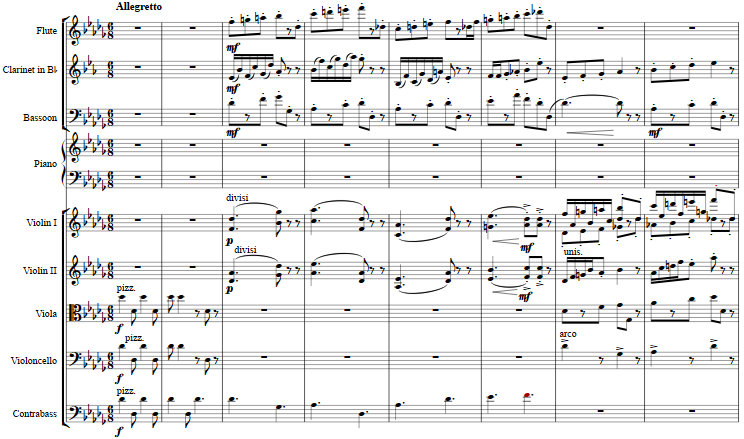

This work for piano and chamber orchestra begins with a first theme, broken major chords in parallel movement challenging the root of D flat. Taken up by winds, then strings and finally piano, it is jovial.

A break from the 6/8, brings a next mood as a 3/4 time adagio, with development and chamber-music-like runs and imitations in the winds and piano.

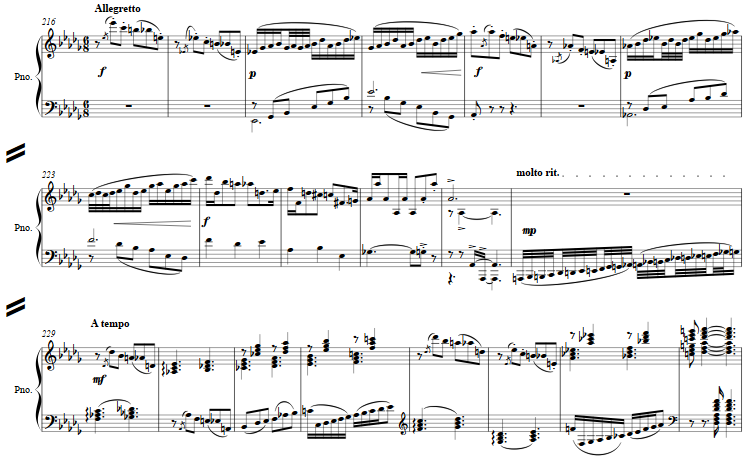

This gives way to moment for solo piano with a return to 6/8, begun with a gesture which spells the musical cryptogram so often used for Arnold Schoenberg and known as set 6-Z44. In the form used, it is E flat, C, B, B flat, E(?), G (= S, C, H, B, E, G). As Leonard Stein was student, assistant, editor and champion of Schoenberg, this little gesture is tribute. Thereafter, the piano introduces what will become one of two fugal subjects which end the work.

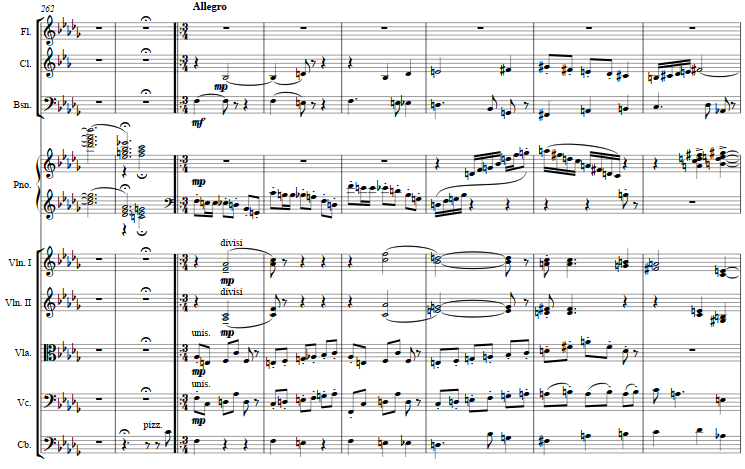

As the orchestra rejoins, echoes of one fugue subject punctuate a statement in bassoon and lower strings which is in fact a twelve-tone row. Set theory which post-dates Schoenberg is not used to manipulate this, but rather tradition "traditional" methods apply. [ 2 ]

A break from the melodic uses of the row, a second musical cryptogram in the piano is stated as fulcrum to a next section. This little snippet -- A, B flat, B, F (= A, B, H, F) for Alban Berg and Hanna Fuchs-Robettin) is from Berg's Lyric Suite. The row is then taken up again, beginning in the high strings, and appears in shifting tonal regions.

A recapitulation of themes combines the "row" in canon with itself over a filigree of arpeggios, with the fugue subject being strongly restated and a last cluster of all twelve tones serves as a brief "dominant" cadential function before the final assertion of the tonal home for the work.

58 pages, circa 15' 30" - an MP3 emulation of the work is here:

The score and parts are available as a free PDF download, though any major commercial performance or recording of the work is prohibited without prior arrangement with the composer. Click on the graphic below for this score.

Concerto in D flat for Piano and Chamber Orchestra

NOTES

[ 1 ] That Stein and Stalvey both were involved for many years in presenting Schoenberg's works in the concert series is appreciated by those who remember that time, now passed. The LACMA presented not only avant-garde concerts, but standard chamber music, a jazz series, and some early music.

As part of a leisurely preparation for the centennial, I read not only Schoenberg's songs with Stein, but others as placing the early work in the context of composers of the era, including Wolf and Strauss. While Stein was open to many strains of music, Stalvey as teacher seemed intent on convincing for a specific aesthetic stance as against others.

For Stalvey, theory was crucial, as he has been working on pieces involving rigorous serialism, and hoped to evangelize others to it. In that time, he was working with serializing not only tones, but durations, articulation, dynamics and other readings of a musical text, such as to further "control" a performer. Yet his correspondence with the likes of Krenek and Noncarrow, as well as his support for jazz programming, suggest that he was perhaps being too much the teacher of theory. Of theory which hinges on a specific aesthetic leaning, Schoenberg observed in Structural Functions: "...no theory can exclude everything that is wrong, poor, or even detestable, or include everything that is right, good, or beautiful."

Stein was more interested in, as he wrote of Schoenberg but which has had for me a broader application, "the resources of an ever-enquiring and constantly growing musical intellect." Given Schoenberg's short association with George Gershwin and generous words at his passing, as an example of differing aesthetic stances, the example is taken.

Stein was for a time curator of the Schoenberg archive, first at UCLA and then when it was moved to University of Southern California. Now the materials have found their way to Austria, and much may be seen online at the Arnold Schönberg Center.

[ 2 ] The now traditional creation of a row has been used in many ways as a way to mine for thematic content. The row employed alongside the musical cryptograms mentioned above for this tribute to Leonard Stein is as follows in its D flat transposition, though other domains are touched:

Over the years, I have referred often to Structural Functions of Harmony. Though a short text in comparison to many, it is effective. Here is the anecdote with which Schoenberg and therefore his editor choose to end the work:

"Hans Richter, the renowned Wagnerian conductor, was once passing by a studio in the Vienna Opera House, and stopped surprised by the unintelligible sounds he heard form within. A coach who had been engaged for this post, not because of his musical talents, but because of a powerful protector, was accompanying a singer. Furiously Richter opened the door and shouted: 'Mr. F--thal, if you plan to continue coaching you must first buy a book on harmony and study it!' Here was a conductor who believed in harmony and in education."

The melding of values "rooted in tradition" in the positive sense as used by Stein, with twelve-tone reference and inclusion of musical cryptograms is hopefully evidence of a "growing musical intellect," in part thanks to an earlier association with the wonderful Leonard Stein.